For the last years, neo-liberal education has promoted an era of post-racial society1 and through a policy of control (the introduction of the National Curriculum, exclusionary agendas such as British Values and Prevent, Ofsted inspection) supports white privilege2.

During the 1980s and 1990s, there was little space to address race equality in education, as the official policy was one of colour-blindness and high standards3. The Race, Racism and Education study conducted between 2013 and 2015 focused on education in England over a twenty-year-period, from 1993 to 2013. The study illustrated that during this period there was strong emphasis on quality and standards, with little attention being paid to social inclusion4.

Moreover, issues of race equality were not seen as important by policymakers after 2010 because they fell outside the scope of quality and standards, but also because policy discourses were seen as de-racialised5, something that had already been addressed.

However, discrimination against minority ethnic groups has been part of mainstream British education for decades and still exists today in more subtle ways6 seen in high stakes tests, performance tables and accountability systems, all of which have been shown to create further social inequalities7.

New racism that emerged in the discourse of the 1970s draws on sociobiological notions of race hierarchies and redefines what it is to be racist. Educational policies during this period focused on cultural differences notions that aimed “to manage and control dangerous others” 8. Policies such as Prevent and British Values framed ethnic minorities as problem groups, unwilling to integrate9, seen as different to the “superior British way of life’10.

Echoing a return to the policy of assimilation11, that wished both to value diversity but also to control people mobility, the preface to the White Paper (2001) clearly reflects this ambivalence in the approach to cultural differences, “to enable integration to take place and to value the diversity it brings, we need to be secure in our sense of belonging’ (2001:1).

Thus, ethnic minorities become evidenced as a ‘problem needing to adapt’12 in education and research shows that discrimination has taken many forms: non-colour racism against Eastern European migrants13, linguistic discrimination in the form of language deficit models of EAL (English as an additional language) students14 , prevent policies aiming to address Muslims seen as “a suspect community” with children as young as four identified as “at risk students”15 and teacher biased assessment16.

This post may contain affiliate links and I may earn a small commission when you click on the links at no additional cost to you. As an Amazon Affiliate, I earn from qualifying purchases. You can read my full disclosure here.

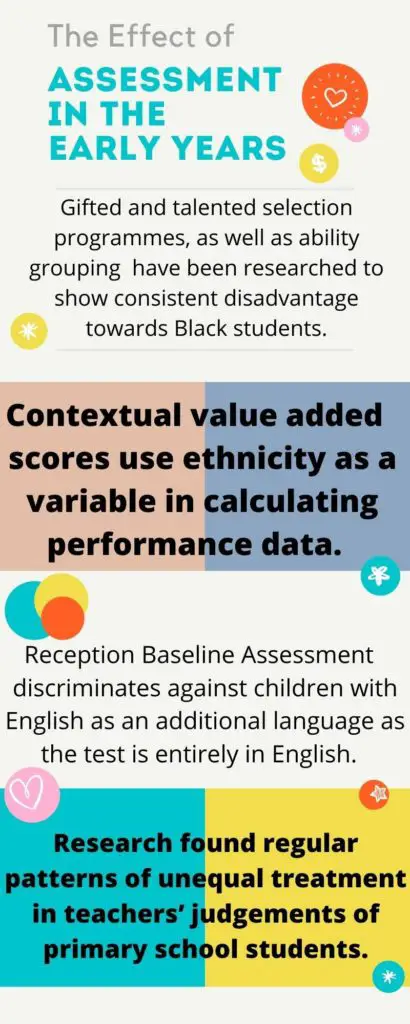

Teacher assessment practices, such as gifted and talented selection programmes and ability grouping, have been researched to show consistent disadvantage towards Black students17 . With the power to assess and rank students in primary schools, teachers overwhelmingly regard Black students with low academic expectations18 , and place them in different intervention programmes.

Contextual value added (CVA) scores and Reception Baseline Assessment are two important measures that shape how children are assessed in early childhood education in the UK.

On the one hand, CVA scores use ethnicity as a variable in calculating performance data, with an impact on pupils’ attainment. Bradbury (2011) analysed the data used to monitor such a measure in primary and secondary schools. Her findings show that a measure promoted as fair by educational policy has the potential to promote low expectations of minority groups in schools. An example of primary schools is given in Bradbury’s study to show how certain minority groups (namely Black Caribbean) make less progress than others, with the implication that through such measures teachers might be encouraged to treat student performance as ethnicity related. Bradbury concludes that CVA is “a legitimisation of differential expectations” (2011:277-291).

On the other hand, the introduction of the reception baseline assessment in the early years sector, a test entirely in English, discriminates against minority groups with English as an additional language (EAL), as any knowledge in the child’ s home language is disregarded. Such a policy establishes low expectations of EAL students from their very first encounter with schools19, in contrast to the existing assessment which recognized children’s knowledge in their home languages.

Through these two measures of discrimination against minoritized groups in the early years sector, racial inequalities are maintained and policy in the name of fairness fails to address diversity in early childhood education.

The case of secondary education system of measures serves as a cautionary reminder that the introduction of new measures aimed to support academic performance can produce a further achievement gap20.

Although educational policies do not intent to be racist, they might produce racist consequences. Gillborn calls this ‘tacit intentionality” (2005:485), the implication being that if policymakers had analysed data from previous policies, they might have been able to predict the racist consequences of a policy21.

Given that in early childhood education children are under assessment with the intent to be labelled in their first years of education22, they become part of a system of measurement and numbers that has the power to classify students into statistics that can “embody the dominant assumptions that shape inequity in society”23.

These first years of schooling serve as an essential element in understanding overall student inequalities24. Gillborn (2016) contends that numbers are not colour-blind, but rather serve as a means to maintain the status quo of White supremacy.

In the UK, policy is based on research and numbers that speak for themselves, a ‘policy as numbers’25 used as a strategy for a fair society. Starting with Margaret Thatcher’s government (mid 1980s to 1997) this fair way of approaching educational policy promoted a colour-blind pedagogy26. Biggs (2019) supports the view that teachers’ choice of such a colour-blind pedagogy may hide racial biases and treatment of students, influencing student expectation and performance.

Learn about early childhood practice and effective learning

By looking at schools as mirrors of society, according to Bakhtin’s concept of heteroglossia (1986), meaning that what we say and think are borrowed from the larger discourse of the community in which we live, teachers might be expected to show discriminatory behaviour against minority groups in schools given that racism is deeply rooted in society27.

Research showed that deficit discourses adopted by educational policy (initiatives that target working-class children, children with English as an additional language) have the potential to “feed into teachers’ differentiated expectations’28. Teachers’ stereotypes are not formed in a vacuum, they reflect the larger social and cultural conceptualizations of minority ethnic groups. Research found regular patterns of unequal treatment in teachers’ judgements of primary school students29.

Burgess and Greaves (2009) analysed long scale observational data of students between the ages of 5 and 14 and found that certain minority ethnic groups (black African and black Caribbean) are under-assessed compared to White students. The study also showed that minority groups, such as poor and Black students, achieve more in tests than in their teachers’ assessments.

In an educational system in which White middle-class students are idealised as models30, ethnic minority groups have the ‘duty’ to raise to these pre-imposed standards of Whiteness, facing an implicit struggle to prove their worth. When education is seen as an economic trade, diversity and complexity are ignored, and it “becomes the individual’s responsibility to succeed in a system that is ‘fair’”31. Adair’s study (2014) of immigrant families in the USA and their relationship with early childhood settings illustrates how responsibility to adjust and integrate is placed on the shoulders of the immigrant.

In the UK, immigrant families are also expected to “perform whiteness in the way British people do”32 with Tony Blair announcing in 2006 that minorities have a duty to integrate.

Learn about the importance of play in the early years

With a focus on returning to core subjects33 and a National Curriculum, there was little space for cultural diversity in early years settings, with plurality and citizenship replaced by British Values34. Narrowing the curriculum to British history, rather than world history, has the effect of exposing children to a dominant narrative that is not reflective of their own identity and “run the danger of thinking that who they are does not matter”35.

Multiculturalism, an attempt to address racial diversity in education, took the form of ‘naïve multiculturalism’, as Connolly refers to the period between 1997 to 2001, when actions to tackle inequalities in education were perceived as ‘superficial and weak’36. This period was followed by a political discourse that either reframed multiculturalism as integration, or even considered the term as being ‘no longer useful’.

More recently (2010-2015), measures of progress in education gained importance, and issues of social inclusion were marginalised37 , progress increasingly being seen as tantamount to effectiveness in schools. Starting with this period, the early years sector witnessed more focus on research involving progress, which had the effect of prioritizing data collection.

Such emphasis on performance has the potential of creating a “disjuncture between this idea of precision and accuracy and the realities of the classroom’38 by reducing and limiting diversity in the classroom.

The long-term effects of such measures could affect children’s identity formation and ‘datafied children’39 could carry the burden of numbers, which as discussed above, are not colour-blind40.

Here are some books to further explore this topic:

References

- Bhopal, 2018

- Barnard, 2020; Bradbury, 2013; Shain, 2013; Gillborn et al., 2018

- Gillborn, 2008

- Gillborn, Warmignton & Demack, 2018

- Warmington, 2014

- Archer & Francis, 2007

- Ball, 1998

- Shain, 2020, p.272-280

- Shain 2013, 2017

- Shain, 2013, p.65

- Back et al, 2002

- Gillborn, 2008, p.73

- Gibson, 2015; Tereshchenko, Bradbury & Archer, 2019

- Campbell, 2015

- Shain, 2013, p.75

- Campbell, 2015; Bradbury, 2019; Burgess & Greaves, 2009

- Gillborn 2008; 2010

- Rollock et al, 2015

- Bradbury, 2019

- Warmington et al, 2018

- Chadderton, 2014

- Bradbury & Roberts-Holmes, 2017

- Gillborn et al, 2016, 158-79

- Warmington et al, 2018

- Ozga and Lingard, 2006

- Gillborn, 2008

- Gillborn, Warmington & Demack, 2018

- Campbell, 2015,p. 538

- Burgess & Greaves, 2009

- Bradbury, 2013

- Sousa, Grey & Oxley, 2019, p.44

- Tereshchenko, Bradbury & Archer, 2019, p.53-71

- Connolly, 1998

- Osler, 2005

- Hindley & Edwards, 2017, p.13-21

- Connolly, 1998, p. 76

- Warmington et al, 2018

- Bradbury & Roberts-Holmes, 2018, p. 12

- ibid:127

- Gillborn et al, 2018

Hi. I am Monica, an experienced ESL teacher and early years student, mother to a preschooler and passionate reader.