One of the problems identified in early childhood education is play and play-pedagogy, a problem that moves beyond the classroom into the home and the community.

It is essential to learn about the importance of play in children’s lives so teachers and parents alike can fully understand their role and impact in offering free play opportunities (free play/ true play/ open-ended play) and help kids’ voices be heard.

Far-Reaching Benefits of Play

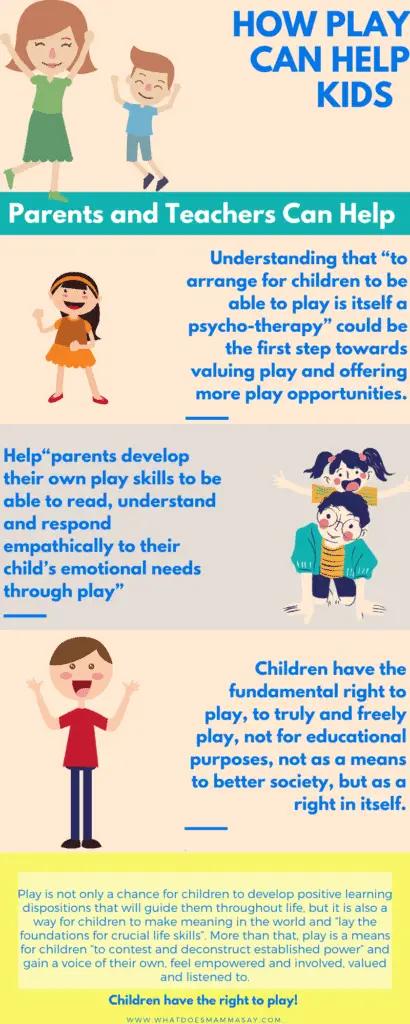

There is extensive research to identify the benefits of play. Play is not only a chance for children to develop positive learning dispositions (Brooker, 2011) that will guide them throughout life, but it is also a way for children to make meaning in the world (Bolton, 1984), and “lay the foundations for crucial life skills” (Rogers, 2011:18)

More than that, play is a means for children “to contest and deconstruct established power” (Wood, 2010) and gain a voice of their own, feel empowered and involved, valued and listened to.

Drawing on play therapy and developmental movement play, we can further develop our understanding of play as a “way of finding resolution and relief from anxiety” (Jones and Elmer, 2009:292), as the play space becomes “an arena to sort, solve and resolve”(Blatner & Blatner, 1988).

Developmental movement play can also ‘enable participants to listen to themselves and their innermost feelings” and “move away from feeling isolated and disempowered” (Filer, 2010:8).

In fact, play therapy argues that a“play shift” can “produce change which can be integrated into the client’s life outside the drama therapy” ( Jones and Elmer, 2009:293).

Play can thus become a powerful vehicle of change within educational settings and at home, as it enables children to express their feelings and deal with difficulties, while at the same time gaining confidence and feeling empowered. These will lead to creating positive learning dispositions, which is one of the main purposes of education.

Anything Which Cannot Be Measured Cannot Matter

But as long as play is commonly seen by parents in ALL cultures as “preparation for life” and “ preparation for school” (Brooker, 2010:39) it is difficult to use free/true play in educational settings and create a bridge between “reflective practitioners understanding the value of play and parents’ belief in the value of education and the role of hard -work” (Brooker, 2010:41).

Given that “parents are likely to identify their children’s progress by means of traditional evidence, a record of work rather than play” (Brooker, 2010:39) using play-based learning in the classroom could prove to be challenging.

One possible consideration for this may be that “anything which cannot be measured cannot matter” (Moss, 2014:66). This in time led to the creation of “evidence-based programmes” and “payment by results” (Moss, 2014).

This standardisation has been shaped by “a story” that “offers a comprehensive worldview about how all human life can and should be reduced to a set of economic relationships and values” (Moss, 2014:63). Peter Moss calls this story the story of neoliberalism, (I will address this in a separate article as it is a complex topic) characterised by competition and inequality.

These two characteristics can be identified in “every facet and niche of life” (Becker in Moss, 2014) and bring about a reductionist approach as “everything can be reduced to monetary value and that value is determined by the interplay of supply and demand” (Moss, 2014:63)

This reductionist discourse has become visible in educational settings as well: ‘the more we seem to know about the complexity of learning, children’s diverse strategies and multiple theories of knowledge, the more we seek to impose learning strategies and curriculum goals that reduce the complexities of this learning and knowledge” (Moss, 2014:41)

Instrumental View of Play

This reductionist and market-style approach to education is further nuanced by how this influences our perception and understanding of free play.

When play is promoted in educational settings, but there are no free outcomes for children, it is hard to perceive the value of true free play because children “cannot have any features or characteristics other than those specified as normal-as defined by their developmental appropriateness” (Moss, 2014:71).

Play in practice is problematic. The British Educational Research Association (BERA) Early Years Special Interest Group (2003) concluded that play in practice has been observed to be “stereotypical and lacking in challenge” and given that “there is no agreed pedagogy of play” (Stephen, 2010:15-28) it is difficult for teachers to engage in a true play-pedagogy and offer true play opportunities. “Work is often disguised as play as early childhood teachers strive to engage children in activities with defined teaching objectives” (Wood, 2005:1-27).

This work-play dichotomy “remains problematic” (Wood, 2014:147) on the one hand because of the “positioning of play as a universal source and driver of learning and development” (Wood, 2014:146) and on the other hand because “free play is difficult to define” (Wood:2014:146).

Adding to this “the under‐development of the pedagogical role of the practitioner in children’s play (Bennett et al. 1997 in Stephen, 2010:15-28) and all the constraints on free play “policy framework, space, time, adults’ role, rules, parents’ expectations, push-down effects from the primary curriculum” (Wood, 2014: 149) it becomes visible that free play suffers great challenges and needs to be addressed as an urgent matter in educational settings.

Use it or Lose it Approach to Early Years Education

This issue becomes even more problematic when a “use it or lose it” (Moss, 2014) approach is applied to early years settings. Knowing that a child’s brain develops at an astonishing rate in the earliest years of life, policy makers are more interested than ever before in using this period as a defining stage in shaping a person’s future success in life, thus making small children part of a “human capital” investment.

“Even in the pre-school phase, play can be seen as preparatory to ‘real’ learning in ‘big school’ and may not be taken seriously by parents or colleagues in school. (Wood,2005:1-27)

The same instrumental view of play can be identified among parents who view learning as a priority “the visible presence of numbers and letters, books and mathematical resources, computers and educational displays are a reassurance for adults that children are learning”( Brooker, 2010:39)

Alongside this shared instrumental view, “parental education, social class and parenting style remain powerful influences, with more effect on school performance than early childhood education” (Moss, 2014: 37)

How Parents and Teachers Could Help Children Play

In light of the above, it becomes clear that both parents and schools play equally important roles in providing children with play and learning opportunities and that these opportunities suffer many influences, with little space for children’s voices to become visible.

Understanding that “to arrange for children to be able to play is itself a psycho-therapy” (Winnicott in Jones & Elmer, 2009:290-312) could be a first step towards valuing play and offering more play opportunities, both in the classroom and at home.

One further step could be to help “parents develop their own play skills to be able to read, understand and respond empathically to their child’s emotional needs through play” (Jones& Elmer, 2009:302).

Just as a reflective practitioner should observe and document play and offer ample play opportunities, so could a parent become a reflective parent and engage in “relationship play”( Filer, 2010) to be able to support a child’s agency and voice that schools encourage/should encourage.

Elizabeth Wood proposes that we look at play from the perspective of what it means for children and explains that these new “lenses will allow the smaller narratives of play to become visible”, thus moving away from a “story” (Moss, 2014) towards “the story of democracy, experimentation and potentiality with its narrative of a flourishing future” (Moss, 2014:15)

Conclusions

Children have the fundamental right to play, to truly and freely play, not for educational purposes, not as a means to better society, but as a right in itself. And I will constantly advocate for this right!

I am now part of a group alongside my brilliant professors to help design a leadership development programme that aims to help schools and teachers and in doing so, making children’s voices visible. Join me in this struggle and help me share my message with more parents and teachers:

Children need to play, it is their right!

References

Waller, Tim, Whitmarsh, Judy, and Clarke, Karen. Making Sense of Theory and Practice in Early Childhood: The Power of Ideas. Berkshire: McGraw-Hill Education, 2011.

Bolton, G. Drama as Education. Harlow: Longman,1984.

Rogers, Sue. Rethinking Play and Pedagogy in Early Childhood Education : Concepts, Contexts and Cultures. London ; New York: Routledge, 2011.

Blatner, A, Blatner, A. The Art of Play. New York: Springer, 1988.

Broadhead, Pat, Howard, Justine, and Wood, Elizabeth Ann. Play and Learning in the Early Years. London: SAGE Publications, 2010.

Brock, Avril, Jarvis, Pam, Olusoga, Yinka, and Dodds, Sylvia. Perspectives on play: Learning for Life. Routledge, 2013.

Filer, Janice. Developmental Movement Play: Moving into Motion to Transform Lives and Well-being: Using Ourselves to Communicate through Movement. 2010

Moss, Peter. Transformative Change and Real Utopias in Early Childhood Education. London: Routledge, 2014.

Stephen, Christine. “Pedagogy: The Silent Partner in Early Years Learning.” Early Years (London, England) 30.1 (2010): 15-28.

Brooker, L. Blaise, M. Edwards, S. Play and Learning in Early Childhood. London: Sage Publications, 2014

Wood, E. Play and Learning in the early childhood curriculum. Los Angeles: London: Sage:3rd Edition:2013.

Hi. I am Monica, an experienced ESL teacher and early years student, mother to a preschooler and passionate reader.